For mainstream jazz artists, and for jazz and pop vocalists from Sinatra to Julie London, the mid-1960s and early 1970s were a period of turmoil. Artists like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Oscar Peterson, Ella Fitzgerald, and Dizzy Gillespie had spent the last decade making the most of the wonders of the long-playing record, allowing them to record tracks that didn’t have to fit on one side of a three-minute 78rpm record, and, even more importantly, to make album-length musical statements. Their popularity had soared, their music had matured, and labels such as Verve, Prestige, Riverside, and Pacific Jazz had allowed them to experiment while, at the same time, throwing their backing behind each disc and giving it the publicity it deserved.

However, with the arrival of The Beatles, and the changes to society and culture through such things as the Civil Rights Movement, everything began to change, and even spiral out of control in the jazz world by the end of the decade. By 1970, singers still at their vocal peak like Doris Day, Julie London, and Jo Stafford would hang up their microphones and record no more albums. Sinatra was about to head into retirement, and wouldn’t record another album of standards for a decade. Dean Martin’s recording career slowly ground to a halt during the 1970s. Sammy Davis Jr got funky and groovy and, after 1974, would only make three more albums before his death in 1990. Bobby Darin turned his back on the Great American Songbook in 1966. Count Basie and his Orchestra would spend much of the second half of the 1960s recording three minute tracks with little room for improvisation, and these would include two albums of Beatles songs, as well as such delights as Oh, Pretty Woman and Do Wah Diddy Diddy. Duke Ellington would record an album of songs from Mary Poppins, as well as the likes of Blowin’ in the Wind and Alfie. Oscar Peterson would try his hand at Ode to Billy Joe and By the Time I Get to Phoenix. Not all artists suffered in the same way. Some would turn their back on the mainstream, and shift their focus into the likes of acid jazz, with various degrees of commercial and artistic success.

It is, perhaps, a little too easy to blame the problems of mainstream jazz artists totally on the change in the pop music field. The LP has been around for well over a decade by the mid-1960s, and one could argue that the songs of the Great American Songbook had been exhausted through the hundreds of albums centring on them that had been produced during that time. Even the likes of Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald could run out of such songs eventually.

Sinatra appears to have made a concerted effort to try to return to the singles chart somewhere around 1964, perhaps buoyed somewhat by the chart success of a song like Hello Dolly by Louis Armstrong or Everybody Loves Somebody by Dean Martin. Certainly, there was success for Sinatra in the pop charts for Strangers in the Night, Something Stupid, and That’s Life. Each of these successes had an album built around them, with the Strangers in the Night LP still sticking to standards for the most part, arranged by Nelson Riddle, albeit in more contemporary-sounding arrangements. That’s Life, on the other hand, was one of Sinatra’s most disappointing albums, consisting of uninspired covers of current tunes in arrangements by Ernie Freeman. The World We Knew, whose big selling point was the inclusion of Something Stupid, was even worse – a couple of good tracks buried among Matt Monro and Petula Clark covers, and the worst version of Some Enchanted Evening you are ever likely to hear.

Sinatra spent the next couple of years “searching” (to use the title of a song he recorded in the early 1980s). He recorded fine albums with Antonio Carlos Jobim and Duke Ellington, an album of country-pop called Cycles, a similar disc built around My Way, an album of songs and poetry by Rod McKuen, and a song cycle called Watertown. For the most part, consumers at the time didn’t get excited over anything other than the Jobim album, despite the fact that there is some excellent work on each of the discs I have mentioned. He continued a series of annual TV specials, but, even here, he could be seen wearing love beads, and trying to duet with the likes of the Fifth Dimension. The retirement of 1971 might well have come about through desperation more than a real desire to quit. When he returned in 1973, the emphasis was more on live shows than on recording. During the next twenty-one years, he recorded just seven albums – and two of those were the uninspiring Duets albums.

Meanwhile, other singers were trying to “get down and with it” with varying results. Julie London, just prior to hanging up her microphone, recorded such gems as the Mickey Mouse March, Yummy Yummy Yummy, and Quinn the Eskimo – all in her trademark “come hither” sultry style. Mel Torme recorded a disc called A Time for Us, which included Midnight Swinger, Games People Play, and Willie and Laura Mae Jones. He didn’t record another studio album until the mid-1970s. That said, A Time For Us has aged somewhat better than some of the similar efforts by Torme’s contemporaries. Never issued on domestic CD, it is available for streaming at the time of writing, and isn’t half as bad as its reputation might lead us to believe.

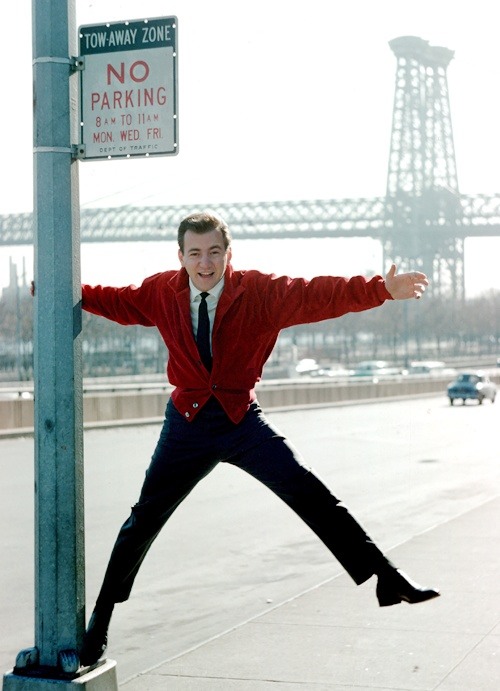

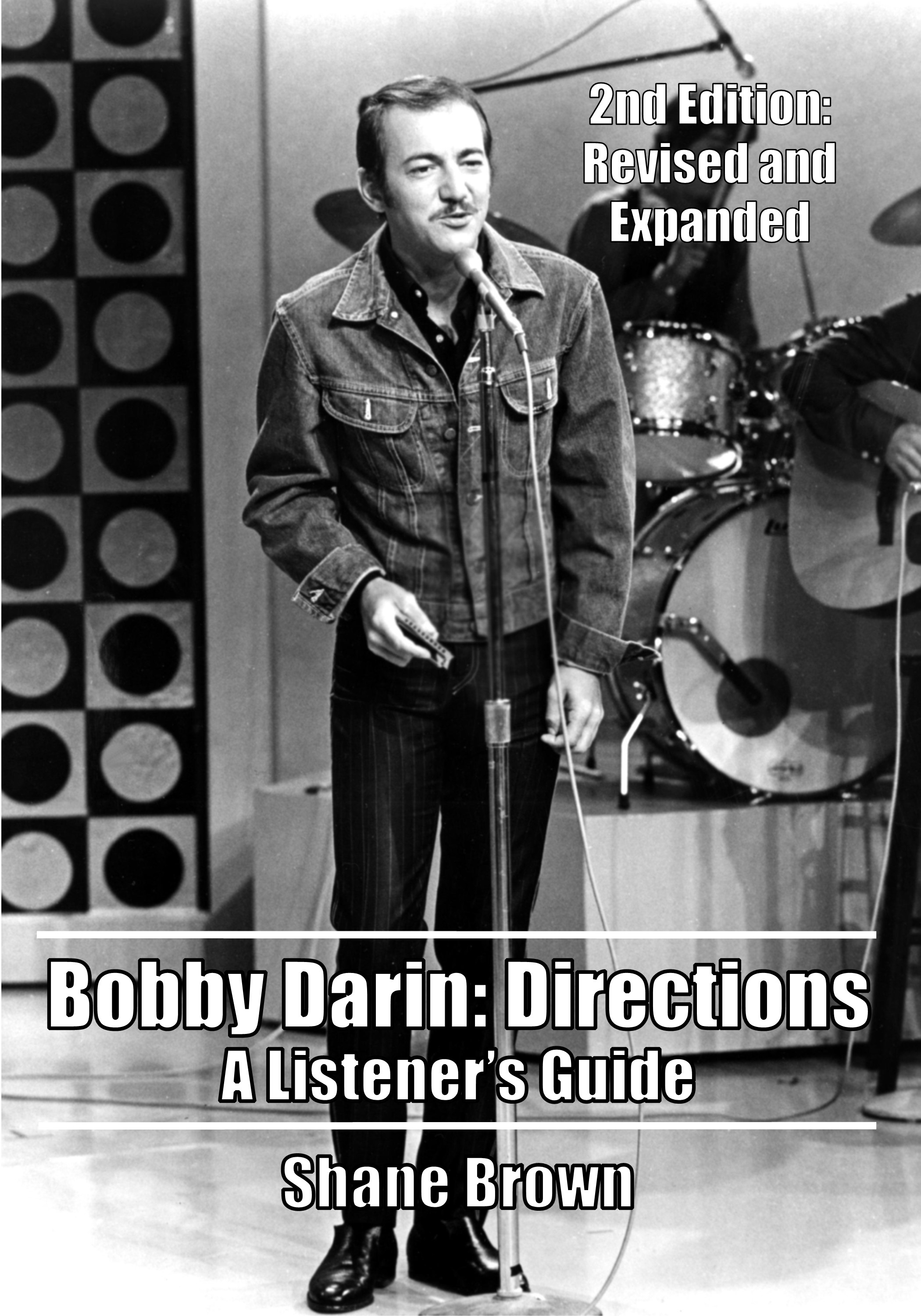

Despite making three of his very best albums in the mid-1960s (The Sounds of ’66, Dr Dolittle, and a guitar and vocal album with Laurino Almeida), Sammy Davis got involved in the counter-culture, but got lost musically. There was some success with I Gotta Be Me, Mr Bojangles, and The Candy Man, but his albums (and clothes) got more and more over-the-top, and he treated his fans to such execrable offerings as his cover of In the Ghetto. Meanwhile, Bobby Darin turned his back on standards following the In a Broadway Bag album in 1966 – unless you want to count the following year’s Dr Dolittle disc. After that, he went into singer-songwriter mode, writing and recording social commentary material – although it’s fair to say that those two albums are actually excellent, and now have a kind of cult following.

Count Basie spent the second half of the 1960s recording albums of standards, and albums dedicated to a particular film soundtrack. But in each case, the tracks lasted just a couple of minutes, and didn’t show off the band to their full potential. The great musicians didn’t have a chance to solo, and the results were easy listening discs instead of jazz ones. He even recorded a number of songs from the pop charts, mostly in poor arrangements, and, it seems now, out of sheer desperation. Duke Ellington also went through that phase during 1965 and 1966, but then seemed to give up trying to be relevant, and so went back to the material he did best. There was a lengthy world tour with Ella Fitzgerald, which would yield several albums, and then he returned to writing and recording long suites, and evenings of sacred music that brought considerable acclaim, even if they didn’t set sales records.

Chet Baker was in a steep decline during the period, and recorded some utterly appalling discs during the second half of the 1960. These included covers of Speedy Gonzales, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, Ring of Fire, and Twenty-Four Hours to Tulsa. These albums with the Mariachi Brass and Carmel Strings weren’t the worst of it, though. In 1968, his teeth were knocked out, and his comeback album was Albert’s House, one of the worst albums you are ever likely to hear, and he followed this up with Blood, Chet and Tears, which featured a pointless (and depressing) version of Sugar Sugar.

Another legendary trumpeter stooped to even lower levels. Louis Armstrong had recorded an album entitled Louis Armstrong & Friends, a rather likeable mix of old and new songs that featured Satchmo working his way through Give Peace a Chance and Everybody’s Talkin’. It might not have been great music, but it was utterly charming. The same couldn’t be said for his next, final album, one which consisted of him mumbling his way through country songs such as Crystal Chandelier and Running Bear. It was probably the most horrible final album in a sparkling career that anyone could think of.

At the same time that all of this was going on, Ella Fitzgerald found herself without a long term recording contract. In the space of six years, she went from Verve to Capitol to Reprise to MPS and on to Atlantic. Despite this, Ella was one of the few jazz musicians that actually thrived when turning her attention to pop songs of the day – perhaps because she had always done it. In the 1950s, she had put in credible versions of Walkin’ My Baby Back Home, Singin’ the Blues, Soldier Boy, and Crying in the Chapel. She was one of the first major jazz artists to include Beatles songs in her repertoire, with Can’t Buy Me Love and A Hard Day’s Night both on Ella albums by the end of 1965. In a period of about seven years after that, she recorded a country album, Christmas album, gospel album, and a rock album. Songs likes Sunshine of Your Love, Spinning Wheel, You’ve Got a Friend, What’s Goin’ On, Hey Jude, Something, Close to You, and Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head were all added to her live performances, despite not being recorded in the studio. Somehow, Ella took it all in her stride and, instead of rebelling against the new music and begrudgingly trying to include it in her work, she embraced it. She didn’t view it as being beneath her, and it’s clear that she thoroughly enjoyed what she called the “now” sounds. Her inclusion of current pop records would slowly fade out during the late 1970s, but she still had time for You Are the Sunshine of My Life and Nobody Does It Better, and a single release of two songs from Chicago.

In the end, it was Ella’s manager, Norman Granz, that came to the rescue of the mainstream jazz musicians. In 1972-3, he set up a label that he called Pablo, which would feature a roster of greats that included Ella, Oscar Peterson, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Eddie Lockjaw Davis, Roy Eldridge, Joe Pass, Milt Jackson, Sarah Vaughan, and more. Pablo didn’t have the commercial clout that Verve or Impulse had, but it was a home for great jazz musicians to make as much or as little music as they wanted, on their own terms, and without any real concerns about how many people bought the albums. This allowed Ella to turn almost exclusively to jazz, rather than mixing it up with pop vocal albums, as she had at Verve.

Also Granz was very keen on mixing things up – putting two unlikely musicians in a room together to see what happened. Ella teamed up with Joe Pass in this way, and Oscar Peterson and Count Basie recorded a series of piano duet albums, despite the fact that their styles were wildly different to each other. Basie thrived at Pablo. For the first time in twenty years, he allowed himself to be recorded regularly in jam session environments (although the big band dates also continued), thus throwing the spotlight on his own piano playing more than had ever happened before. Sadly, Duke Ellington passed away in 1974, but one can only imagine what he would have achieved at Pablo had he lived.

Pablo’s budget was small – the artwork for many albums was atrocious – but if I had to choose the recordings of any one jazz label to take to a desert island, it would be Pablo’s. It was a wonderful home for so many artists entering the final phase of their careers, but who were still producing great music, and it must have seemed like a sanctuary to them after the turmoil of the previous seven or eight years.

Suggested discography:

The following albums are not necessarily recommended, but are examples of the type of output discussed in the article.

Louis Armstrong and his Friends (Flying Dutchman)

Chet Baker: Blood, Chet and Tears (Verve)

Count Basie: Basie’s in the Bag (Brunswick)

Bobby Darin: Commitment (Direction. Under the name “Bob Darin”)

Sammy Davis Jr: Something for Everyone (Motown)

Duke Ellington Plays Mary Poppins (Reprise)

Ella Fitzgerald: The Sunshine of Your Love (MPS)

Julie London: Yummy, Yummy, Yummy (Liberty)

Oscar Peterson: Motions and Emotions (MPS)

Frank Sinatra: Cycles (Reprise)

Mel Tormé: A Time For Us (Capitol)

It’s hardly surprising that viewpoints on this album vary wildly. For fans of Ella’s jazz material, it’s a waste of talent. For fans of country music, it’s a weird mish-mash of styles. But, let’s be honest, Ella had never been JUST a jazz singer. In fact, she had wrapped her tonsils around country music before, such as A Satisfied Mind back in 1955, and much of her material from the early to mid-1950s wasn’t jazz either, with her tackling the likes of Crying in the Chapel and Soldier Boy during those sessions. And, throughout the 1960s, she incorporated some of the “now sounds” (as she called them) into her albums and concerts, including Beatles tracks and the likes of Walk Right In. So, really, this country album didn’t come completely out of left-field.

It’s hardly surprising that viewpoints on this album vary wildly. For fans of Ella’s jazz material, it’s a waste of talent. For fans of country music, it’s a weird mish-mash of styles. But, let’s be honest, Ella had never been JUST a jazz singer. In fact, she had wrapped her tonsils around country music before, such as A Satisfied Mind back in 1955, and much of her material from the early to mid-1950s wasn’t jazz either, with her tackling the likes of Crying in the Chapel and Soldier Boy during those sessions. And, throughout the 1960s, she incorporated some of the “now sounds” (as she called them) into her albums and concerts, including Beatles tracks and the likes of Walk Right In. So, really, this country album didn’t come completely out of left-field.