Sometimes a story is told so many times that we believe it without questioning it. We’re all guilty of it – and it is particularly true when it comes to showbiz stories. However, in 2015, some of these oft-told tales simply fall to bits thanks to the availability of primary documents such as newspapers, magazines and trade journals through online archives. Take, for example, the story of Irving Berlin’s apparent anger towards, and hatred of, Elvis Presley’s recording of White Christmas in 1957. We have been told many times over several decades that Berlin tried to get the recording banned and/or that he tried to persuade DJs not to play it. But is it really true?

There are a number of myths told and retold about Elvis’s White Christmas recording. The first of which is that it used the same arrangement as the recording by The Drifters a few years earlier. While Elvis clearly models part of his vocal on the earlier version, the arrangements are far from the same.

The opening of the Drifters take on the song starts with backing vocals, whereas Elvis’s starts with a basic piano and guitar introduction. The backing vocals continue throughout The Drifters’ version, but Elvis opens the song without backing vocals at all, and the backing vocals on his recording are far more restrained than on The Drifters version. In fact, the work of the backing vocalists in the two versions are VERY different indeed. In the first run-through of the song, Elvis sings the “may your days” section in a straightforward, traditional manner, but the Drifters do not – they sing this section in the same manner as Elvis’s repeat of this verse. The Drifters repeat the entire song – Elvis only repeats the second half, this time employing a vocal line very similar to the Drifters. The Drifters version contains other instruments, such as the use of an organ, for example, and their recording ends rather differently to Elvis’s too. So, rather than Elvis copying The Drifters arrangement, he simply uses their vocal line for the repeat section.

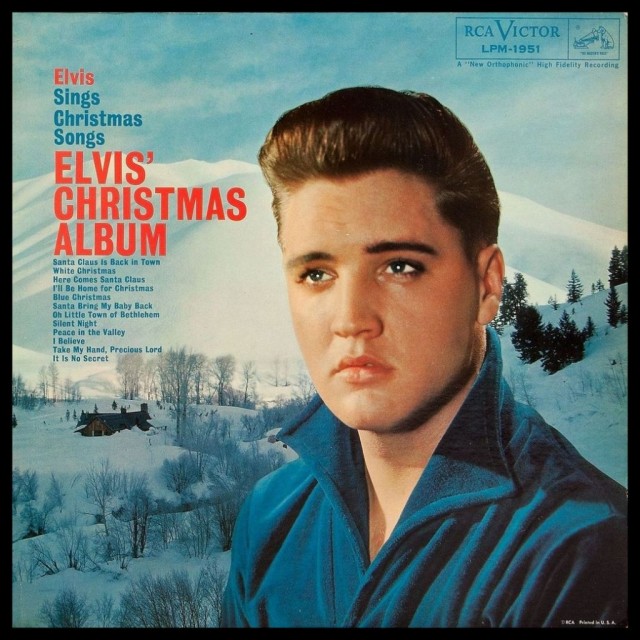

One story that certainly is true is that the Christmas album received largely negative reviews when it was released. One writer in the Ottawa Citizen review called the album “a masterpiece of seasonal miscasting,” and that it was “ludicrous and pathetic.” However, the interesting thing here is that the album isn’t given a poor review by this writer because he or she is shocked by Elvis, but quite the reverse. “Most of the time,” the review reads, “he’s so hushfully reverent in his approach to these unfamiliar themes that he just isn’t there at all.”

Despite the review in the Ottawa Citizen, the album certainly fell foul of censorship, with certain radio stations banning the playing of the album totally, and others banning White Christmas in particular, with one radio station official in Canada referring to the LP as “degrading” in an interview with Variety on December 4, 1957. At least one DJ was fired for breaking a ban on playing the album, according to reports (although even this is now debatable).

It is certainly true to say that there are many articles about the album in trade journals and both local and national newspapers in 1957. So this, surely, is where we can find the first mention of Irving Berlin trying to get White Christmas banned? No, is that answer to that. In fact, the story doesn’t seem to appear at all anywhere until 1990 when Laurence Bergreen included the anecdote in his acclaimed biography of Irving Berlin, As Thousands Cheer. There, we are told that, on hearing the recording for the first time, “he immediately ordered his staff to telephone radio stations across the country to ask them not to play this barbaric rock-and-roll version.” In the notes for the book, Bergreen lists an interview with Walter Wager as the source of the information. Wager was a novelist and, later, an executive of ASCAP – and yet there are questions raised here as to how Wager knew this information if he wasn’t with Berlin at the time – and there is no indication that he was. In fact, this could easily have been a story that Berlin told to him at a later date, and that Wager then repeated in the late 1980s to Bergreen.

The story really entered the Elvis world in 1994 with the release of the CD If Every Day was Like Christmas. Here, the story from the Berlin book is regurgitated in Charles Wolfe’s liner notes. Since then, it has been taken as the truth – and why not? There was nothing at the time to suggest that the story was false, exaggerated or inaccurate. It has been repeated many times since then, most recently in the liner notes for the FTD edition of Elvis’ Christmas Album and, yes I admit it, my own book Elvis Presley: A Listener’s Guide (none of us are infallible!). We don’t question these stories until something suddenly makes it fall apart – and the thing that makes it fall apart is that there is no mention of it until 1990.

We live in a world now where there are many free online archives of newspapers and magazines, and even more that are not free or only available to researchers and academics. This allows us to go back and see how things were reported at the time – and that’s exactly what I wanted to do about a year ago. But there was a problem. This story, in which one of the most respected songwriters of the 20th Century tried to ban a recording by the new sensation Elvis Presley, was nowhere to be found in these publications. Not in Billboard or Variety, not in the New York Times or Washington Post, not in fan magazines, not in regional newspapers. There was/is no logical reason why such a huge story would not have been reported in some (or all) of these publications – unless it never happened. This would have been big news, and would have been picked up by the trade magazines and journals at the very least. And we should also remember that Berlin was having more than his fair share of publicity in 1957 because it was the 50th anniversary of his time in show business – even more reason why such a kerfuffle would make the news.

But there was nothing. Until 1990.

The only source for the story is that interview with Walter Wager that Bergreen used for his book – every other retelling of the story stems from that, not from other witnesses or interviewees. Sadly, it is a fact that interviewees are often unreliable, and this is something we are discovering more and more now that we can go back and check facts ourselves with relative ease. Why would Wager twist, exaggerate or lie? Sometimes, it appears that interviewees tells us what we want to hear, or memories are dimmed and foggy thirty years after the events. Or perhaps Berlin told him the story and Wager was simply repeating it – and it was Berlin who was exaggerating or fabricating a good tale. What is clear, however, is that Berlin never did set in motion an attempt to get the recording of his beloved White Christmas banned.

Perhaps there is a nugget of truth somewhere – that, perhaps, Berlin wanted to ring those radio stations but was advised against it, or he thought it would bring too much unwanted attention to the recording, or perhaps the royalty cheques were just too tempting. We will never know the answers to these questions. But, thanks to the ongoing digitisation of our recent past, we do know that neither Berlin or his staff made those calls.

[…] the book got the information from a man in the entertainment industry named Walter Wager. However, there is no further source to back up Wager’s claim. Nevertheless, other people wrote about their discontent with the […]

Hi. I’m not sure how this adds anything to either my article here or on EIN, which the Elvis News story links to, Both discuss the Wager issue and how no-one can back up his claim, and that he wasn’t with or around Berlin at the time.